Roman Road System In Britan

The Roman road system in Britain, built 2,000 years ago, was seriously impressive.

It was one of the most impressive and lasting monuments to the nearly four centuries (AD 43–410) that the island of Britannia was a province of the Roman Empire.

Designed primarily as a strategic tool for conquest and control, these engineered highways became the backbone of civil administration, trade, and communication, fundamentally shaping the geography of Britain for nearly two millennia.

It is estimated that the Roman army built and maintained approximately 2,000 miles of paved trunk roads across the province, connecting legionary fortresses, burgeoning towns, and key ports with remarkable efficiency.

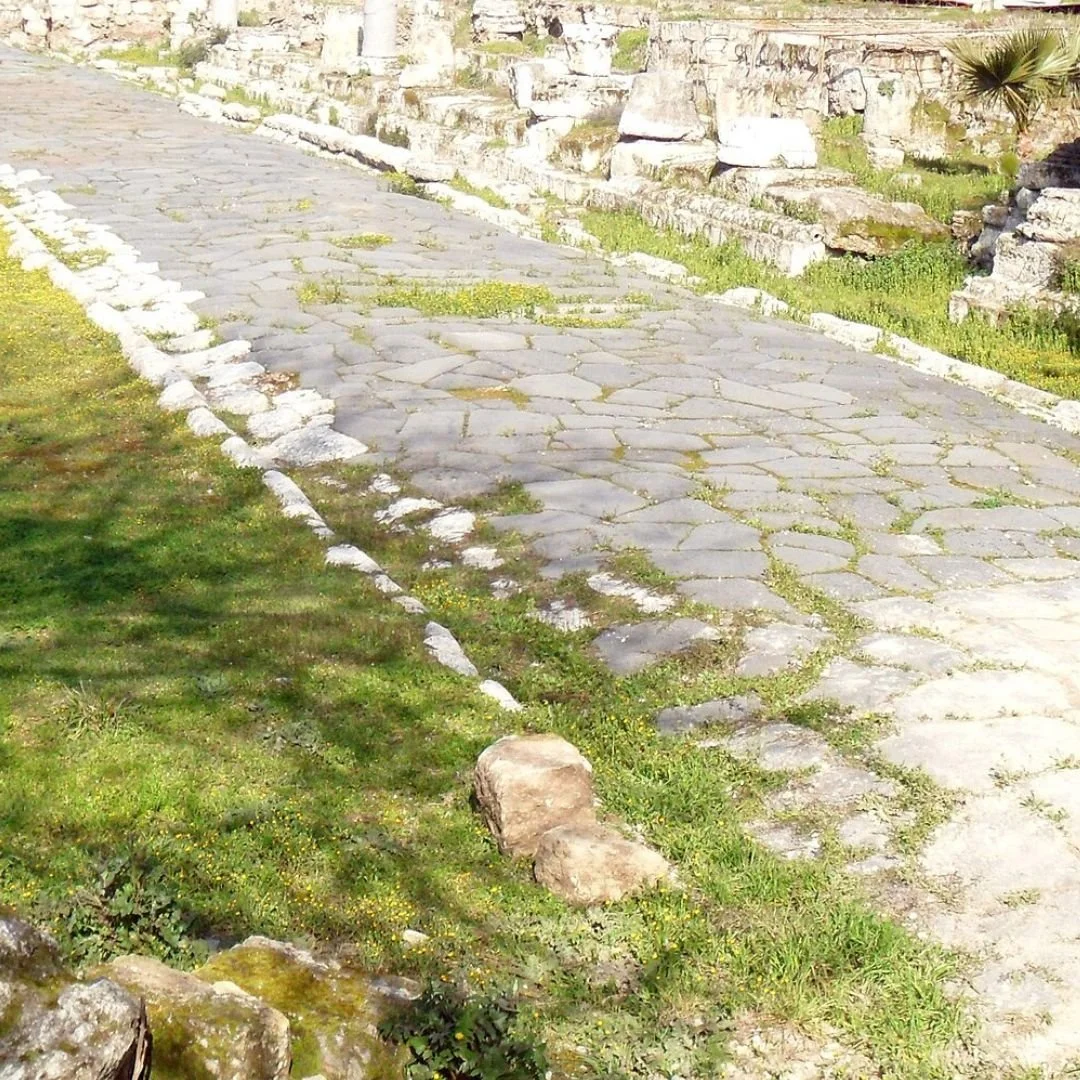

Excavated segment of the Fosse Way, Somerset

Before the Roman arrival, Britain’s inhabitants primarily relied on unpaved trackways, often following the high, dry ground of prehistoric ridgeways.

The Romans, however, demanded something far more robust: direct, all-weather arteries capable of moving legions and supplies quickly, regardless of the season.

The construction of a via munita (paved road) was a major civil engineering feat, typically overseen and executed by the Roman army.

The process adhered to long established Roman standards, featuring several key elements.

Agger: The road was built upon a raised embankment, or agger, formed from excavated earth, which ensured the road was well-drained and visible across the landscape.

Drainage: Ditches were dug on either side of the agger to collect water, helping to keep the foundation dry and stable.

Foundation and Surface: The roadbed consisted of multiple compacted layers. A base of large stones and rubble was laid first, followed by successive layers of smaller stones, gravel, and sand.

The final surface was typically fine compacted gravel or, in high-traffic urban areas, tightly fitting cobbles. The surface was also cambered (higher in the middle) to aid water run-off.

Straightness: Roman surveyors were masters of direct alignment.

Using tools like the groma (for setting right angles), they plotted courses as straight as possible, often only diverting to avoid major geographical obstacles like mountains or deep marshland, or to link with strategically important settlements.

The earliest roads were built in the initial decades of the conquest (AD 43–68), linking the invasion ports in the south-east with early legionary bases and the new capital, Londinium (London).

As the frontier expanded north and west, so too did the network.

By AD 180, most of the major trunk routes were complete, forming a cohesive system centred on London.

Travel on Roman roads in Britannia was a diverse affair, catering to the needs of the empire from rapid military deployment to the slower pace of civilian commerce.

The primary modes of transport were on foot, by horse, or by wagon/cart.

For the military, legions would march at a disciplined pace, typically covering 18-25 miles per day, even with heavy packs and armour.

For the most urgent imperial dispatches, the cursus publicus (Imperial Post) operated a sophisticated relay system using fast horses and staging posts (mutationes for changing horses, and mansionesfor overnight stays).

This allowed couriers to cover exceptional distances, potentially exceeding 50 miles in a day. Civilians traveled on foot, often at a pace of 15-20 miles daily, relying on the same roadside inns.

Goods were moved by ox or horse-drawn wagons, which were significantly slower, averaging perhaps 8-10 miles per day.

To illustrate, a journey from Isca Dumnoniorum (Exeter) to Londinium (London), a distance of approximately 170 Roman miles, would have taken:

Imperial Courier: As little as 4 days by continually changing horses.

Roman Legionary (marching): Around 7 to 9 days carrying full kit.

Civilian on Foot: Between 8 and 12 days, allowing for overnight stops.

Wagon or Cart (for goods): A much more arduous 17 to 22 days.

These estimates highlight the efficiency of the Roman road system, enabling the relatively swift movement of personnel and information, which was vital for governing and defending the distant province of Britannia.

Roman wagon (reconstruction)

Many of the most significant Roman roads were given their distinct names centuries later by the Anglo-Saxons, but their original routes remain central to Britain's infrastructure today.

The initial purpose of the road system was, overwhelmingly, military: to facilitate rapid deployment and keep the legions supplied.

However, they soon served the needs of the cursus publicus (the imperial postal and communication service) and, increasingly, commerce.

Villas and towns often grew up along the network, and goods like pottery, grain, and iron ore were transported across the province.

Pottery, especially, was exceptionally popular and ubiquitous in Roman Britain, essential for both daily living and as a key commodity in the provincial economy.

Even after the official end of Roman rule in 410 AD, the Roman roads remained the best-managed and most direct routes in Britain.

For over a thousand years, they continued to function as the skeleton of the country's communication and transport system.

In many places, the foundations were so well laid that they simply formed the basis for modern highways, a direct link between the ancient world and the UK's national road network today.

The Main Roman Roads of Britain

Fosse Way: Ran from Isca Dumnoniorum (Exeter) to Lindum Colonia (Lincoln). This road initially marked the effective boundary of the early Roman province, running in a remarkably straight line across the country's heartland.

Large parts of the A46, A429, and A37 follow its line today.

Watling Street: One of the earliest and most vital roads, connecting Durovernum (Canterbury) and the key ports of entry (like Dover and Richborough) to Londinium, and then extending north-west to Viroconium (Wroxeter) and eventually Deva Victrix (Chester).

The modern A2 and the A5 largely trace its path.

Stane Street

Stane Street: Connected Londinium with the important southern port of Noviomagus Reginorum (Chichester), another early and strategically crucial route in the south-east.

Much of the modern A29 in West Sussex retains its ancient name and alignment.

Roman Roads vs. the Modern UK Network

While the Roman roads laid the foundational grid for transport in Britain, the modern UK road network presents a very different contrast, in both purpose and design.

Roman roads prioritised straightness and speed for military movement, often ignoring local topography, which made them effective for rapid north-south/east-west connections.

Today's network, particularly the motorways, retains this core principle of direct connectivity (e.g., following the M5 or M1), but the engineering is dictated by the requirements of high-speed, high-volume traffic and modern safety standards.

Modern roads feature gentle curves and gradients, sophisticated banking, and complex junctions, necessitated by motor vehicles.

Crucially, the Roman network was primarily a trunk route system, whereas the modern UK network is a vastly more complex, interwoven tapestry, with millions of miles of secondary and residential roads that serve daily commuter and distribution needs far beyond the simple A-to-B garrison connections of Roman Britannia.

If you enjoyed this blog post, please follow Exploring GB on Facebook for more!

Thank you for visiting Exploring GB - don’t forget to check out our latest blogs below!